How Artist Iris Häussler Inspires People to Save Birds

The show Divided Heavens at the McMichael Gallery in Kleinburg, Ontario, explores the theme of bird migration and the dangers of windows

Iris Häussler was five years old when she started finding dead birds. She grew up in Germany near Lake Constance, an agricultural area known for growing hops. It was the 60s, when DDT was all the rage, and Häussler often wandered the fields after they were sprayed. As she traversed the rows, the plants sticky with chemicals, she would find poisoned birds and butterflies. These experiences etched themselves into her memory — and eventually her art.

“My artistic practice is in giving voice to something that's often overlooked,” she says.

Häussler channels this voice into her immersive installations, which revolve around fictional characters of her creation. She has shown in museums around the world, but she’s best known for exhibiting in unconventional spaces. Her first site-specific installation was in 1984 at the women’s restrooms in the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and she has since exhibited in churches, trailers, apartments, hotel rooms, stores, industrial buildings, monasteries, historic houses, and garages.

“It feels more inclusive than the white cube”, explains Häussler, who wants artwork to be accessible and relatable. Galleries, she says, can sometimes intimate people.

In June 2025, Häussler undertook an artist’s residency at the McMichael Gallery in Kleinburg, Ontario. Located on 100 acres of forested land, the McMichael is a major public gallery of Canadian art, known for its collection of Group of Seven works.

Häussler was invited to create an installation in the historic Tom Thompson shack, which served as the home and studio for the iconic Canadian painter Tom Thompson from 1915 to 1917. Originally located in Toronto, the shack was moved to the McMichael grounds in 1962 when the City of Toronto threatened to tear it down. Today, it serves as a creative space for artists in residence.

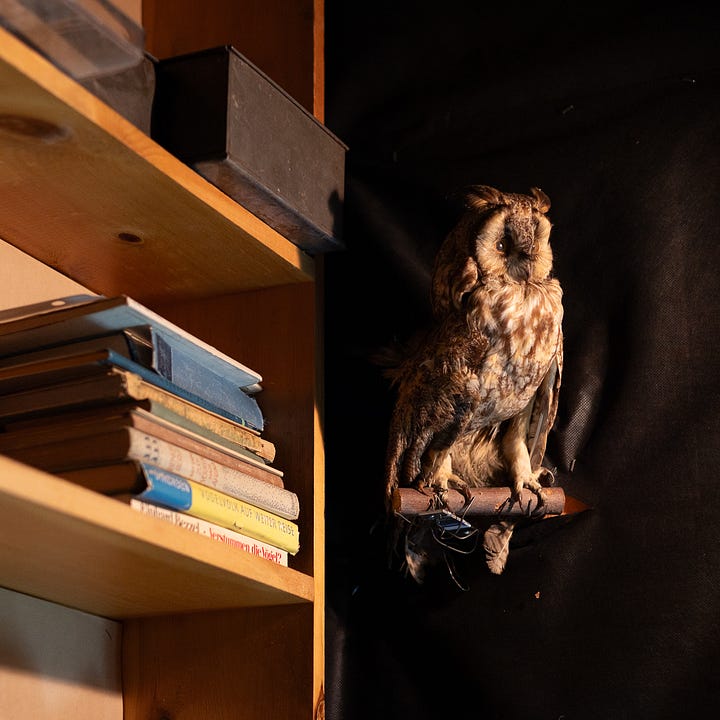

The Tom Thompson Shack consists of two areas : a small, dark, wood-panelled den and a large, sun-filled room. Artists in residence typically use the former to create, to relax, and to store their working materials. But Häussler made it the heart of her installation.

“It's dark, it's intimate, and I don't think you would get that same feeling from the main, lofty space,” she says. “I wanted to contrast both rooms.”

The installation, named Divided Heavens, explores the fictional world of Kurt and Carl Pfister, German-born twins who were separated after their father was killed in World War II. The brothers grew up unaware of each other’s existence, yet shared a passion and empathy for migratory birds. Each twin expressed his bird obsession in a different way, and the exhibit combines their creations and collections. (For the full story, check out Häussler’s book Divided Heavens by John Geoghegan and Sarah Milroy.)

The exhibit feels like a cabinet of curiosity. In the small room, there are bookshelves lined with ornithology texts, globes adorned with strings that trace migration routes, and panes of glass etched with migration pathways and bird imprints. In the main space hangs a large mobile made of cut out bird illustrations. As they twirl and sway in the breeze, their once-living counterparts lay under a glass case, reminding us of their fragility. Encased in glass and killed by it, these specimens send a message about the danger that windows pose to birds.

Indeed, collisions with buildings are a leading killer of migratory birds. Between Canada and the United States, window collisions kill at least a billion birds every year in North America. Birds can’t tell the difference between glass and reality. If they see a reflection of the sky or trees, they perceive it as real; if they see a large plant through a window, they think they can fly into it. The only way to make a window safe is to treat it with markers (like decals) that show birds that it is a solid surface. To be effective, markers need to be spaced at least 2 inches apart or less, be placed on the outside surface of the glass, and be high enough contrast to show up against strong reflections. (For more on this issue and how to prevent collisions, see my article for Chatelaine.)

Häussler witnessed collisions firsthand in 2014 during a residency at the Odette Center at York University, and talked with staff and a few professors about retrofitting the buildings (which has been done on some of the facades). She also volunteers for FLAP, a Canadian charity dedicated to making the built environment safer for birds. Volunteers patrol the streets, looking for collision victims. Dead birds are collected for research and logged in the Global Bird Collision Mapper. Live birds (which are rare) are sent to the Toronto Wildlife Centre for rehabilitation.

While Häussler’s art isn’t advocacy per se, it sends a powerful message and sparks memories. After experiencing the installation, many visitors have talked about seeing a bird collide with a window, or finding a dead bird. These recollections offer an entry point for Häussler to discuss the issue and suggest actions people can take to make their homes safer for birds.

“That's when the magic happens,” she says. “When you have a conversation.”

I was there to witness the magic happen. As I was photographing Häussler in the shack, a couple walked in, and she gave them a tour. They were deeply moved by her art, and talked about how they have witnessed birds fly into the window of their cottage. They wanted to do something, but were unsure how to go about it. With warmth and enthusiasm, Häussler talked about different ways they could treat their windows — and encouraged them to take action. Before leaving, the visitors pledged to make their windows safe.

Sadly, even when people want to help birds, they often hesitate to put anything on their windows. They worry about how it will look, what the neighbours will think, or whether decals will ruin their view. Häussler addresses this barrier in a way that no one else does: creating artistic, custom window installations for people’s homes and cottages.

Since most people can’t afford custom installations, Häussler teaches people how to make their own artistic decals. She has run workshops at the Toronto School of Art, the Prince Edward County Art Lab, the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), the Art Gallery of Mississauga, and most recently, the McMichael. She has partnered with landscape architect Victoria Taylor to teach how to create bird-friendly habitats in our gardens — and make sure the birds they attract don’t collide with windows. After giving a talk on the issue, Häussler guides participants through a freehand drawing exercise to create unique shapes on paper. These are transferred onto self-adhesive vinyl foil, cut out, and playfully arranged into patterns. Participants can take them home, peel off the backing, and put them on their windows or glass railings. Some have even sent her photos of how they treated their windows.

Rather than lecturing or shaming, Häussler inspires people with her art, provokes empathy, and fosters creativity. Her approach not only breaks the taboo that windows are untouchable — it encourages people to treat their windows like a canvas. All to save the precious lives of birds.

Häussler admits that it can be a big leap from inspiration to action, but she seems to have found the right recipe:

“It takes people being encouraged, in a state of courage, in a state of urge, in a state of exploration, experiment, and joy.”

Divided Heavens is on until September 28. Book your tickets here.